Perhaps one of the better movie quotes within the past two years has come from the 2011 movie “Margin Call.” In it, an investment bank is followed as the American financial system begins its precipitous fall to worthlessness. John Tuld, one of the executives of the bank, played by Jeremy Irons, explains, “There are three ways to make a living in this business: be first, be smarter, or cheat.”

Indeed, it seems as if high school education is the same way. To extend the metaphor, the business Tuld spoke of equates to being admitted into college, or so a high school student may think. Admission into the establishment of their choice depends on being the first, being the best, or cheating to compensate for their lack of ability in the two former categories.

In a sense, the idea of cheating is not so much immoral as it is animalistic. Darwin taught us all that the fittest beings survive in their environment most successfully. If an adolescent’s environment is a paper on character analysis, or a test on cell reproduction, wouldn’t it be fulfilling of our animalistic side that we try and gain an edge? It’s only natural that we attempt such cheating. Rectification of the institution of cheating would come better from other sources.

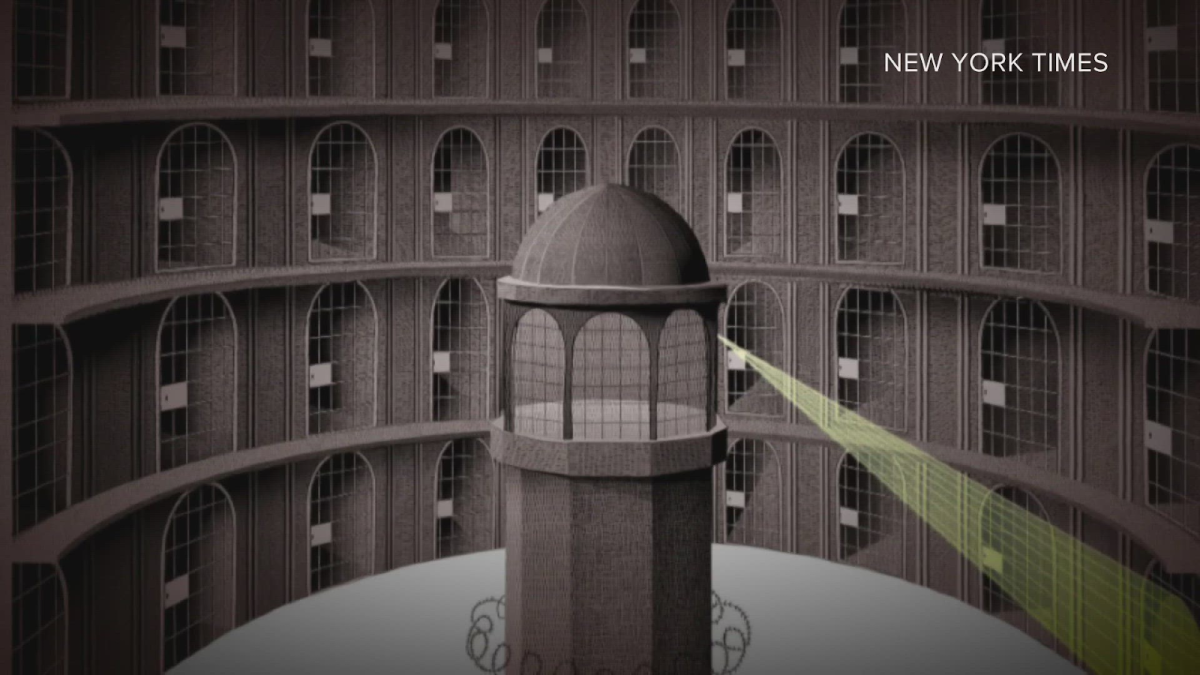

Certainly, there are impediments to cheating already: Turnitin for instance, or strict proctoring. Yet a great number of students are smarter than an algorithm, and current computational science believes this will be the case until 2050. One would think that teachers would understand this, and proctor their exams with the utmost of scrutiny. Yet this remains to be seen. Simple observation would reveal that teachers might take testing time to catch up on emails or grade other classes. This gives students—whose morals are only being formed within the years of adolescence—the ability to take out their small piece of paper to cheat off of, or take out the iPhone with the power of Google at their fingertips. One would think cheating on school-given standardized tests, such as the PSAT or Terra Nova would be nonexistent. Yet strict proctoring does not fully prevail in those environments either. Rather than watching students, teachers may take out their laptops, leaving students ample time to take a glance at an adjacent student’s answers, or flip back to another section.

It is both idealistic and unrealistic to think that students becoming moral can solve cheating. The human race has never been entirely scrupulous, and educators cannot expect high school students—the epitome of immaturity—to listen to their inner-moral being. The world today is not the same as it was thirty years ago—students literally have all the answers to the test within their pocket. If one is to expect cheating to be curbed, those who proctor exams must be more vigilant: close the laptop, monitor the students. Perhaps you will teach your students a lesson or two, so they don’t grow up to be like John Tuld.