Perhaps the most harrowing images World War II left the world are those of Nazi Germany’s Concentration and Death Camps. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, an estimated 11 million people died in Concentration and Death Camps: 6 million Jews and 5 million Non-Jews—Roma and Sinti, resistance fighters, Gays, Jehovah’s witnesses, and more (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum). Understandably so, humanity has sworn to prevent such an atrocity from occuring again. However, as history has reminded historians time and time again: people never learn and are bound to repeat themselves.

Though the concept of concentration camps did not begin with the Nazis in 1933, the idea has and will continue to persecute the human race. Concentration camps have long been accredited to the twisted minds of Hitler’s trusted advisors and, like most of the ideology that defined the party, the concept was stolen.

The Introduction to Concentration Camps

The first nation recorded to implement concentration camps are the Spanish. In 1895, 3 years before the events of the Spanish-American War, Spain was stuck in the middle of a war with Cuban rebels who refused to submit to Spanish rule. Governor-General Arsenio Martínez Campos wrote to Spain from Cuba that the only way Spain could come out victorious was to “inflict new cruelties on civilians and fighters alike”. To isolate soldiers from any civilian support, Martinez Campos believed the solution to be the relocation of hundreds of thousands civilians into Spanish-held territory behind barbed wire. Martinez Campos referred to the strategy as reconcentración (Smithsonian).

General Martinez Campos would change his mind, however, when the rebels showed mercy to Spanish wounded and returned prisoners of war unharmed. Martinez Campos could not fathom implementing the process of reconcentración on an enemy he viewed as honorable. Martinez Campos resigned his post and sent a letter to the Spanish Crown: “I cannot, as the representative of a civilized nation, be the first to give the example of cruelty and intransigence” (Smithsonian).

In his place, on February 10, 1896 Spain sent General Valeriano “The Butcher” Weyler. “If he cannot make successful war upon the insurgents, “ wrote the New York Times in 1896, “he can make war upon the unarmed population of Cuba” (NY Times). In 1896, General Weyler of Spain implemented Martínez Campos’ Reconcentration Policy. By 1898, one third of Cuba’s population had been forcibly admitted into the camps. They were crowded into dilapidated and rotting houses where food was a luxury; famine and disease, specifically yellow fever and dysentery, quickly spread through the camps (PBS). In 1896, the Cuban population was 1.8 million. By 1898, the population decreased to an estimated 1.57 million (Digital History Textbook). Over 400,000 Cubans died as a result of the Spanish Concentration Policy (Smithsonian).

Mass detention had always existed: the Native Americans in the United States being forced onto reservations; the Natives in Ireland being forcibly removed and relocated by the English; the Devil’s Punchbowl in Mississippi where over 20,000 newly freed enslaved blacks died of starvation and disease after the Civil War (Nineteen Fifty-Six Magazine). Sidenote: historians now use the term “concentration camps” to describe the atrocities that occurred in the examples listed above. The list goes on and on. However, Spain marked a new beginning: a different approach to mass detention. The detention of Cubans in Spain was the first time the term “concentration” was explicitly used.

In 1898, in a call to arms before Congress, President McKinley spoke of the Spanish Reconcentration policy: “It was not civilized warfare. It was extermination. The only peace it could beget was that of the wilderness and the grave” (Smithsonian).

Eventually, the United States would be embroiled in a successful 10 week war with Spain. After presumably helping free the Cubans from Spanish rule, the United States amassed an impressive list of war spoils: possession of Spanish Colonies and some autonomy in Cuba. What would come to develop in the Philippines was unexpected by Americans. A revolt was underway: the Filipinos wanted liberation. In 1901, in response to the resistance, the United States would force the people of the Philippines into concentration camps. Upon seeing one of these camps, an Army Officer wrote, “It seems way out of the world without a sight of the sea,—in fact, more like some suburb of hell” (Smithsonian).

Whilst the Spanish concentration camps were well underway, and the United States deliberated over the implementation of camps themselves, a different nation was taking action in another part of the world. In 1900, during the Boer War, Great Britain began the process of relocation. Over 200,000 women and children were forced behind barbed wire into tents or haphazardly built huts. Similar to Martinez Campos, many Britons were plagued with the moral violation that the concentration camps appeared to be. “When is a war not a war?” posed British Member of Parliament Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman in June 1901. “When it is carried on by methods of barbarism in South Africa” (Smithsonian).

Between 1899 and 1902 over 48,000 Boers died in the camps; 80% of them children (The Conversation). The Boers of South Africa were farmers and miners. They were white descendants of the British Empire who went to war with Great Britain over British desire for the precious jewels and minerals of the region. The Boers died as a result of polluted water supplies, lack of food, and infectious diseases. The British Public was outraged. An estimated 14,154 of Black Africans died in even more squalid living conditions (United Kingdom National Archives). Though the public took less notice of these deaths. The Boer War ended in 1902, but the use of camps continued.

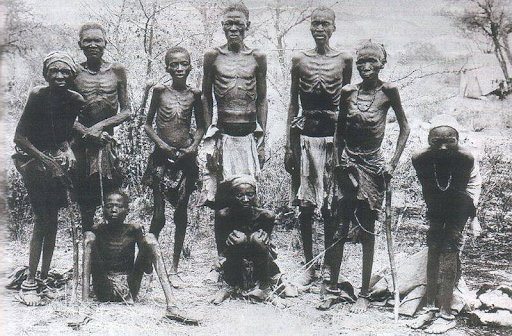

In 1904, in a neighboring German colony of Southwestern Africa—modern-day Namibia—, General Lother von Trotha declared an extermination order for the Herero people, who had rebelled against the Germans. Civilians, children, soldiers, rebels, farmers, women, and innocents alike were killed with the same ferocity. The order was shortly recalled soon after, but the remaining Herero and Nama people were herded into concentration camps. In these camps they would face forced labor, starvation, fatal diseases and near extermination. By 1907, a lethal combination of German policies killed over 70,000 Namibians (Smithsonian).

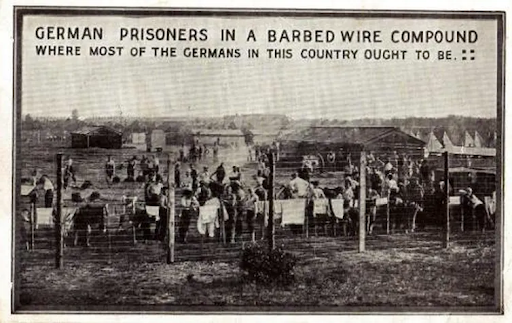

The camps continued to be used, but they became a solution to a problem that rushed a new age in Europe: World War I. As the nations of Germany, Austria-Hungary, England, France, the Soviet Union, and the Ottoman Empire ordered the conscription of any military-age male, the future for German immigrants in England became skewed. To prevent the immigrants from being deported and returning to Germany to fight, Britain found a more sinister solution: incarceration (Smithsonian). On August 5, 1914, a day after declaring war on Germany, Parliament passed the Aliens Restriction Act: alien residents of military age(17-42) from enemy nations were rounded up and forced into camps. British Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith stated that the physical removal of these aliens would protect them from harm from the British public, while ensuring national security (Oxford University Press).

In 1915 The British expanded internment to its foreign territories. The Germans began the mass arrest of aliens from allied countries. Other countries followed suit and the use of camps became essential to modern warfare (Smithsonian).

Across the pond, in the United States, more than two thousand prisoners—Germans and Austrians alike—were contained in camps. During the Great War, letters and packages were received by prisoners. A bureaucracy of detention grew where Red Cross inspectors would visit and make humanitarian reports—an aspect of camps that would become well-known during World War II (Smithsonian).

By November 11, 1918 over 800,000 civilians were held in concentration camps. Though the concentration camps present during WWI were more civilized than its predecessors, not all camps during the war passed inspection (Smithsonian). In 1915, the Ottoman Empire used a system of concentration camps, lacking sufficient food supplies and shelter, to deport Armenians into the Syrian desert in an organized genocide. Over 1.5 million Armenians of the 2 million initial population were killed; the Armenian people would travel to Syria through brutal death marches. By 1922, only 400,000 Armenians remained (NY Times).

Polish-Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin researched the tragedy and in his book would be the first to describe it as a “genocide.” In 1943, he would coin the term (NY Times).

Following the end of World War I, from the 1920s to the mid 1950s Stalin’s Soviet Union would establish the Soviet Gulag: a system of labor, detention, prison, and transit camps that held over 5 million political prisoners(from WWIII, during the war) and criminals, ethnic groups, members removed from the “newly-purged” Communist Party, and innocent civilians (Britannica). The camps would end up killing over two million people (The Times).

Similar to the British during World War I, the United States established “internment” camps during World War II. In 1942 President Franklin Delano Roosevelt enacted Executive Order 9066 which ordered the immediate removal of thousands of Japanese Americans in the Pacific Coast (HISTORY). From 1942 to 1945 10 “relocation centers” were opened, holding a total of 120,000 prisoners (Britannica).

Why Does This Matter?

The essential question at the end of a lengthy article: so what? Other than being relevant to current events,—the repression of over 1.2 million Uyghurs in China in concentration camps (whoops, I meant “re-education” camps), is one example—the history shows the cruel extent of human nature (BBC).

More importantly, the history of concentration camps gives an unclear answer to a question you may have: What about the good guys? and Do good guys even exist in history? As Ms. Hollman often repeated in class: “History is never black and white because people aren’t black and white.” To think that people, events, and historical figures could even be organized in these binary categories of good and bad is, frankly, naïve. But the human desire to simplify complicated matters to the extent that they lose their original meaning (like a twisted game of telephone) prevails in the 21st Century. Take one of the many events of 2020: the Black Lives Matter Movement. In the United States, as a result of the Black Lives Matter movement, many historical statues were removed (including some that glorified the more morally skewed figures of history, yikes)—either by force through an angry mob, or at the request of said angry mob. Were we assessing history with an unbiased eye or were we, rather, judging the events of the past through modern values? The answer is clear: there are no good guys and, yes, some Americans have a bad case of presentism. The past is frozen; we cannot change what happened and the way the public reacted. In this modern age, we have to pick and choose our battles. We can try to make ourselves feel better about what previous generations did, but no protest will change the fact that slavery existed in the United States until 1865 or that 6 million people died in the Holocaust. We can memorialize and teach our children to learn from our mistakes, but the past cannot be changed.

If history has taught us anything, it is to remain critical and hold nations accountable. In remaining apathetic we inadvertently excuse the atrocities and give our silent permission. When speaking of the dangers of silence, Nobel Peace Prize Winner Archbishop Desmond Tutu said, “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor. If an elephant has its foot on the tail of a mouse and you say that you are neutral, the mouse will not appreciate your neutrality.”