By: Tasha LaChac

Ah, the Pledge of Allegiance. It’s something so common practice in America, most students have been reciting it since they were in kindergarten.

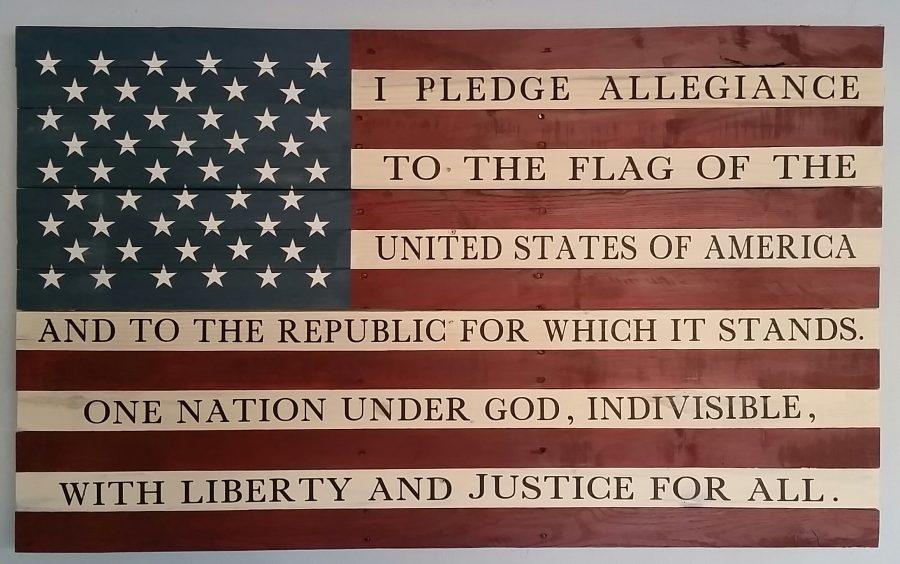

The Pledge goes like this: students stand up, put their hands on their hearts, look at the flag, and pledge their allegiance to it. The words can vary slightly, but the modern phrasing is as follows: “I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America. And to the Republic, for which it stands, one nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

American students have been reciting the Pledge for so long in the classroom, and even beyond, that it seems commonplace. Routine. And therein the normalcy lies the danger. The Pledge of Allegiance is outdated and unethical, and shouldn’t be used in schools any longer.

***

It is important to understand the origins of the Pledge of Allegiance to dismantle why its dangerous . So, where does the Pledge come from? It was first introduced in the United States in 1892. The original Pledge read roughly the same, but instead of “I pledge allegiance to the flag” the text was “I pledge allegiance to my flag.”

The decades of the 1880s and 1890s saw an influx of a new wave of immigrants to the US, coming from more of southern and eastern Europe, whereas before immigrants had mainly arrived from northern and western Europe. This new type of immigrant sparked nativist sentiments, which further provoked a call for stronger demonstrations of patriotism. There were calls to make the Pledge mandatory in schools, supported by aggressively patriotic groups like the Daughters of the American Revolution and the Grand Army of the Republic. Right after the declaration of the Spanish-American war in 1898, the state of New York’s legislature issued a mandatory order for schools to salute the flag at the beginning of each day.

World War I pushed the desire for the Pledge even further. There was an idea of “100% Americanism,” which celebrated American ideals while pushing down foreign ideals. Extreme patriotism in tandem with xenophobia made the Pledge evermore popular. The Pledge was spread even further, becoming commonplace in schools. There were no protections on cultural diversity written in the Constitution which might protect an immigrant child from reciting the Pledge. Some schools used this terminology to their advantage, using the Pledge to “denationalize” immigrants, especially German immigrants. As a result, students found it difficult to refuse to pledge their allegiance to the flag.

People were so worried about foreign invaders that around this time, the words to the Pledge were amended. The original had read “I pledge allegiance to my flag,” with no “of the United States of America,” but some worried that that was too vague. There was the idea that a child could be saying “my flag” when they pledged, but instead of thinking about the United States, they were secretly pledging to their mother country’s flag. The words were subsequently changed to “I pledge allegiance to the flag, of the United States of America.”

World War II renewed the sense of fear that WWI had introduced, and brought with it two landmark cases for the Pledge of Allegiance. The first was Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940). In this case, two children who were Jehovah’s Witnesses were expelled for refusing the pledge on religious grounds. The Court ruled in favor of the school, reflecting wartime fears of the 1940s.

However, this ruling was later reversed with West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943). This time, the Court ruled that it was the student’s First Amendment right to refuse to say the Pledge. It dictated that a state could not constitutionally require students to pledge to the flag. Justice Robert Jackson specifically asserted that the right to a nonpartisan, free public education was paramount over any so-called problems of “national security” people claimed that not saying the Pledge would cause. (Ironically, the ruling was announced on Flag Day.)

***

Barnette was a cornerstone case in protecting students rights that’s still valid today, and that could be the end of it. What, then, was the point of that history lesson?

Well, for starters, this isn’t just history. The Pledge of Allegiance, which started in the 1890s, is still alive and well in schools today, and thrives now for many of the same reasons it thrived in the past. Look no further than 9/11, the after effects of which drove the War on Terror and a new wave of xenophobia. There is a cycle here, one which perpetuates fear and hatred of outsiders. The Pledge – which itself is based in a tradition of prejudice – asks students to swear themselves to a country that has a rocky history, ethically speaking; it asks them to swear themselves to the United States at a young age before they can comprehend what they are swearing, and it has them repeat this oath every day.

These are difficult topics to grapple with, and ones that easily make people uncomfortable with pledging themselves to a country with a history of immoral actions. Thus, it makes sense that a student might choose to exercise their right not to pledge. Theoretically, students are already protected from having to pledge, yet despite the student-protecting precedent of Barnette, conflicts still occur.

Take Elk Grove School District v. Newdow (2004), where the Supreme Court refused to address whether or not the words “under God” were constitutional. The First Amendment to the Constitution guarantees freedom of religion, so it seems both unethical and illegal to require students to pledge to a deity that they don’t believe in. Under some religions, pledging to the flag is not allowed because that would be to swear their allegiance to a flag, which is not their god and therefore a false idol. Even so, the Supreme Court did not rule to strike down the words “under God,” and thus schools may

still legally have students pledging to something that goes against their religion.

Or look at Frazier v. Winn (2008), where a board policy in Florida requiring a student to stand during the Pledge unless excused by a parent was challenged. The Court ruled that the students could remain seated and silent, but it was legal to require parents to be notified should their child choose not to participate. This is hardly freedom of choice at all; schools are supposed to foster learning and independence, yet a student’s fundamental freedom of speech – which in this case is entirely protected, as it harms no one – is limited by their parents. Despite historic cases that seem to protect students rights to not say the Pledge, modern policies that challenge students are a very real and current issue.

Even if there were no official consequence to not reciting the Pledge, the social pressure a student faces if they are the only ones not pledging may, in some schools, be enormous. If the choice to not pledge isolates the student, then it is hardly a choice at all.

***

The real solution is not to allow students to refuse the Pledge if they wish. It has been shown that the freedom of choice is all too often taken away from the student. No, the real solution is to get rid of the Pledge of Allegiance altogether.

The Pledge has its roots in xenophobic nationalism. It conditions students to unthinkingly pledge their allegiance daily to a country that has, undeniably, done bad things. No, patriotism is not a bad thing, but the Pledge of Allegiance is not patriotic. It instead reinforces the dangerous idea that citizens should be loyal without question to their country, and at some point, blind patriotism will cross the line into chauvinism.

In 1916, an eleven year old black child named Hubert Eaves was arrested for not reciting the Pledge. He said that he was uncomfortable pledging his allegiance to something that, to him, symbolized Jim Crow laws and lynching. Eaves said; “ ‘I am willing to salute the flag… as the flag salutes me’ ” (O’Leary, Cecelia, and Platt). One hundred years later, the flag of the United States of America does not salute everyone within its borders. It’s an uncomfortable truth, but one that cannot be ignored. It’s been long enough – the time for schools to abandon the Pledge of Allegiance in history is now.

Works Cited

“First Amendment.” American Law Yearbook 2009: A Guide to the Year’s Major Legal Cases and Developments, Gale, 2010, pp. 100-106. Opposing Viewpoints in Context, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CX1347000052/OVIC?u=jchs_ca&sid=OVIC&xid=31b191b5. Accessed 24 Aug. 2018.

Montgomery, Jennifer J. Controversies over the Pledge of Allegiance in Public Schools: Case Studies Involving State Law, 9/11, and the Culture Wars. ProQuest LLC, ProQuest LLC, 01 Jan. 2015. EBSCOhost.

Nielson, Erik. “Patriotism Should Not Be Promoted in US Schools.” American Values, edited by David M. Haugen, et al., Greenhaven Press, 2014. Opposing Viewpoints. Opposing Viewpoints in Context, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/EJ3010110402/OVIC?u=jchs_ca&sid=OVIC&xid=17c20182. Accessed 24 Aug. 2018. Originally published as “Stand Up for Liberty by Sitting Out the Pledge of Allegiance,” Huffington Post, 2013.

O’Leary, Cecilia, and Tony Platt. “Enshrined Patriotism Endangers America.” Is It Unpatriotic to Criticize One’s Country?, edited by Mary E. Williams, Greenhaven Press, 2005. At Issue. Opposing Viewpoints in Context, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/EJ3010354205/OVIC?u=jchs_ca&sid=OVIC&xid=4ae79519. Accessed 24 Aug. 2018. Originally published as “Pledging Allegiance: The Revival of Prescriptive Patriotism,” Social Justice, vol. 28, Fall 2001, p. 41.

Russo, Charles J. “Controversy over the Pledge of Allegiance Continues.” School Business Affairs, vol. 76, no. 3, 01 Apr. 2010, pp. 36-38. EBSCOhost.