Our collective consciousness has engaged in an extremely unhealthy obsession with itself. When reminiscing on the past year, one can not help but dwell superfluously on the strife that the year 2016 brought. When I think of the pervasive pessimism of 2016, my mind goes to Syria; a race for presidency filled with acrimony and vitriol; Brexit; surpassing 400 ppm in carbon emissions; the shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando; the deaths of unarmed black men such as Alton Sterling, Terence Crutcher, and Keith Lamont Scott; a myriad international terrorist attacks; and countless more. However, I would also be remiss to shuffle around the passings of colossal musicality, it has to be noted.

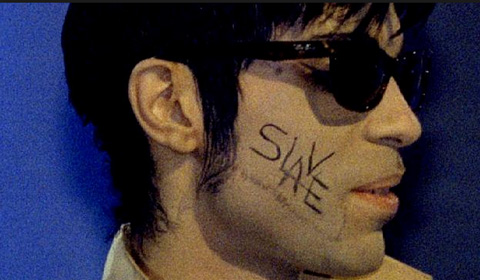

Last year exhibited a sense of surrealism, knowing that the hearts of Leonard Cohen, George Michael, Keith Emerson, Prince, Phife Dawg, etc. all stopped beating. Their art, which we have come to experience, has always been unconsciously fortified by the fact that those artists are alive, with the back of your mind echoing “they share the same air that I do” when listening in awe to their music. Then this subtle comfort is quelled when they die–there will be no more tours, no more albums, no more shared reality of living.

We become devastated, then loss piles onto loss and we become spiteful and full of malice. We blame the year, the anthropogenic construct to measure a bigger construct: time. There is undeniably folly evident here, and we can surely cope through other means. To elaborate, a dichotomy needs to be addressed as we digest the excessive loss of musicians from last year. The tragedies that have been so prominent that they created our perspective on 2016, can be examined and split as inevitable and preventable. This is where we then need to digress a bit further. While the former includes the what was once fast approaching rise above the 400 ppm carbon emissions marking, the latter includes the killings of unarmed black men such as Terence Crutcher and Philando Castile.

The overall effects of this dichotomy coalesce and we arbitrarily assign our defiled sentiments to a unit of time, rather than an extensive look at how we are as a society. The deaths of the many musicians we came to know over the years fall into the “inevitable” category. We are so obsessed with our loss that we forget the ubiquity of music, especially music we deem satisfactory.

All music deemed such will not be vaporized into nonexistence after a musician dies. Good music has always existed and will never die. These artists like Prince or Cohen pass away and we almost forgot the most solidified effigy a musician can offer: the album. Cohen’s Songs of Love and Hate drove away any despair of his loss I could have fallen into and A Tribe Called Quest’s entire discography did the same with Phife Dawg’s passing. Their art does not live on after they die; rather, their art lives as them. Relentless deaths of musicians only mean “their time has come”. Their deaths are only part of their lives, as is yours, as is mine.

Perhaps the American public could learn from their southern neighbors rather jubilant holiday El Dia de Los Muertos. This holiday serves as reconnection to lost loved one through community dancing and parading in the street, visiting the tombs and giving gifts to them, eating meals with the tombs, gathering with family, eating festive treats, etc. Perhaps if our country relearned how to view death, we wouldn’t feel so burdened by the losses of musicians in 2016. I would probably feel less alienated about my reactions if this were the case. In a way I have said goodbye to Prince, George Michael, Leonard Cohen, and Phife Dawg, yet I have not truly said goodbye to anyone. Everytime I relisten to the heart-wrenching closing chorus to Diamonds in the Mine by Cohen–“For there are not letters in the mailbox, for their are no grapes upon your vine, for there are now chocolates in the boxes anymore, and there are no diamonds in the mine”–Cohen is there with me. 2016 didn’t take him away from me. I move forward with purpose and character, and their art only reminds me of that.