The War on Drugs

February 12, 2023

“Today, cocaine is found throughout our society, from top to bottom, and that means corruption from top to bottom:” An In-Depth Analysis of The War on Drugs, Drug Epidemic, and US Involvement in Drug Trafficking

When prompted to opinionate on the causes of the prevalence of drugs in poor communities, many will reason that this occurrence is a result of exactly what it appears on the surface: poverty and the minorities that inhabit the cities. However, this belief is inaccurate and accusatory, and fails to acknowledge the complexity of drugs’ grip on a federal scale. In fact, there is no causal relationship between addiction and income levels. There is, however, correlation. The strikingly low income levels in Afrocentric and Latin majority cities create stressful, impoverished environments, which increases feelings of hopelessness, decreases self-esteem, and decreases social support (Addiction and Poverty: Is There Really a Correlation?). All of these factors and many more contribute to the turning to drugs as a coping mechanism (Addiction and Low-Income Americans).

Often, poor Americans are blamed for their own addictions, but the root cause of increased drug usage in poor communities runs deeper and traces back to the North American crack epidemic of the late twentieth century.

The idea that the US government has contributed to the trafficking and commodification of illicit drugs has gripped the nation’s attention for decades, especially among Latin and Black Americans. Some speculate that the CIA itself intentionally flooded the inner cities, targeting African-American and Latino communities. That being said, it is widely believed that the government shares some responsibility in the drug trade. When assessing the validity of this belief, it is essential to understand the history of the peddling of narcotic drugs. The start of the drug trade is muddled and complex, worsened by the popularization of the internet in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

A Not-So-Brief History of American Involvement in the Drug Trade

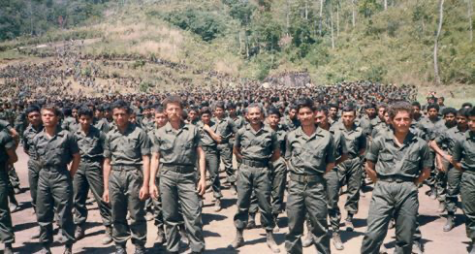

The theory of the CIA’s involvement in the drug trade first appeared in the 1980s with the emergence of the cocaine epidemic in the United States. However, the history of North American narcotic involvement traces back to the jungles of Central America, specifically Nicaragua. In 1979, the Somoza regime, a dictatorial government, was overthrown by social revolutionaries called the Sandinistas. As a result of this uprising, right-wing rebel groups known as the Contras began a brutal paramilitary campaign. The Contras were funded by the US and received money and weapons from the CIA as a part of the Cold War struggle against the Soviet Union (VICE). In 1987, in his remarks to the 100th annual Convention of the American Newspaper Publishers in New York, President Ronald Reagan (1981-1989) famously justified American involvement in Nicaragua: “If we cut off the freedom fighters, we will be giving the Soviets a free hand in Central America, handing them one of their greatest foreign policy victories since World War Two”(US National Archives). It was made clear to the American public that the US is the good guy fighting against the bad guys to save the poor helpless Latinos in Nicaragua. This oversimplified narrative, however, could not be further from the truth. By 1982, it was clear that US involvement would evolve into the unthinkable.

In 1982, Democrats in Congress passed laws to cut off support for the Nicaraguan rebels. Clearly, the Contras and their CIA supporters would have to find a new method of funding their political

aspirations: cocaine. In the late 1970s, more people in the US were snorting cocaine in unprecedented numbers, most of it imported from Colombia. In the early ‘80s, smokable cocaine or crack exploded across American cities. By 1982, over 10.4 million Americans were addicted to cocaine (PBS). The industry proved to be a goldmine for countless organized crime groups, including those backed by the CIA.

Soon after 1982, the Contras became involved with Colombian cartels. And in 1985, reporters Robert Parry and Brian Barger released an unbelievable and groundbreaking story: Nicaraguan rebels were involved in cocaine trafficking, and not only did the CIA know of these activities, they permitted these criminal activities to continue to help fund the Contras’ war effort. According to Nicholas Schou, journalist and author of Kill the Messenger (a novel, now available as a movie adaptation): “When Bob Parry and Brian Barger got a hold of a CIA report revealing that they were working in the mid-1980s with Contras fighting the Sandinista government, they were warned by their editors that this was not something that was going to make the people that own their newspapers very happy, and both of them ended up losing their jobs” (Schou). Following the publication of Parry and Barger’s allegations, the CIA strongly denied involvement in the drug trade. However, the rumor that the government was either actively or passively allowing crack to be sold spread like wildfire among the American public. Many admonished believers of these allegations as unpatriotic and conspiracy theorists.

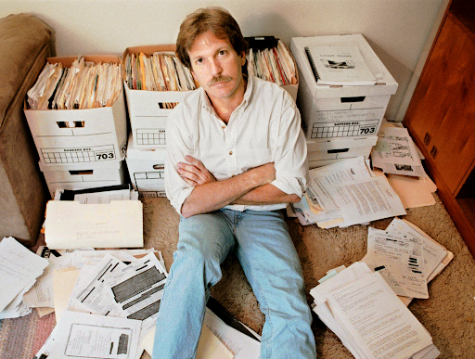

Parry and Barger’s allegations would remain just rumors until 1996 when reporter Gary Webb of the San Jose Mercury News dove deeper. Webb investigated the case of Freeway Rick Ross. In the early 1980s, Ross was the most important kingpin in L.A.’s crack scene and is considered to be America’s first-ever crack millionaire. Ross, incidentally, became the first black American involved with the cocaine trade and was directly involved with informants in Nicaragua. Webb uncovered that Ross’ primary cocaine supplier was a man named Danilo Blandón, a Nicaraguan exile who funneled tens of thousands of dollars in cocaine profits back to the Contras through banks in Miami. Blandón worked for Norwin Meneses, the biggest drug trafficker in Nicaragua, who had deep ties to the Contra leadership and is widely believed to have benefited from CIA protection. In 2006, journalist Nicholas Schou published the widely-acclaimed novel Kill the Messenger. The novel outlines Gary Webb’s investigation and the consequences he would bear for publishing his findings. Schou explained the situation regarding Menses at the time: “The Drug Enforcement Administration(DEA) had always tried to arrest Norwin Meneses, who was living openly and raising money for the Contras, but had never been able to build a case against him and felt like there was something about this guy that must explain why they couldn’t do that, that he was protected, in other words. And when Gary Webb’s story came along, he not only showed where the connection was between Menses and Blandón and “Freeway” Ricky Ross, but he also went into all this history and unveiled how there was a very large, well-documented crack distribution ring that had operated for years with the CIA turning a blind eye”(VICE).

In a 2014 interview on the Jim Norton Show, accessible on the VICE website, “Freeway,” Rick Ross explained his involvement in the crack trade:

Jim Norton: What’s the process you go through? You’re the guy on top, and where do you get your coke from?

Ross: I was getting my coke from a guy by the name of Oscar Danilo Blandón, who also was my informant. He’s the guy that set me up with the police. When I went to trial, we found out that he was what they call a Contra. The Contras was backed by the CIA. And it spawned this investigation by this reporter called Gary Webb.

In August of 1996, The Mercury News published Webb’s reports in a three-part series titled “Dark Alliance.” The story went viral and became particularly popular in the African-American community, which had been targeted by law enforcement following the rise of crack.

In a 1996 interview on the Montel Williams Show on CBS, Gary Webb explained the focus of his publications: “It was about the cocaine rings that operated along the West Coast of the United States throughout most of the 80s. And some of the money they were making would support an army that the men who ran the cocaine ring worked for called the FDN. This was the army that the CIA started in 1981 and supported. [Better known as] the Contras”(VICE).

Nowhere in “Dark Alliance” did Webb explicitly assert that the CIA was responsible for the crack epidemic nor that they intentionally sold the drug. However, this was the narrative many Americans came to believe was true. Webb’s story took off not only as a result of his scandalous claims but also because the internet enabled a new level of coverage and viral speculation. “Dark Alliance” was one of the first substantial publications of investigative journalism accessible simultaneously in print and digitally.

The reaction of the American public was explosive and chaotic. Unprecedented times, however, called for unprecedented measures. CIA director, John Deutch, took to defend the agency at a controversial tense L.A. community meeting: “It is an appalling charge that goes to the heart of this country. I will get to the bottom of it, and I will let you know the results of what I found” (VICE). Soon after Deutch’s naïve declaration, an unidentified black woman famously questioned his promise: “How are we supposed to trust the CIA official to investigate themselves?”

Indeed, there was little trust in the tumultuous relationship between the United States government agency and the African-American community. However, all would soon be forgotten as a deadly display of the CIA’s media control would ravish the life of Gary Webb.

Webb and the San Jose Mercury News have explained to readers that “Dark Alliance” was intended to start an in-depth investigation. This investigation could then be furthered by larger newspapers with more resources and funding.

Instead of investigating the CIA, the mainstream press like the L.A. Times, Washington Post, and New York Times attacked Webb. Webb was forced from his job as the lead journalist and could not continue his work as a journalist. In 2004, Webb committed suicide (Kill the Messenger).

Nicholas Schou explained the media frenzy that erupted from Webb’s publication: “All three major newspapers felt completely caught off guard by this story, so they fully attacked Gary Webb with a vengeance, unlike anything that had ever been seen before, and completely attempted to not only discredit his story and frame it as a conspiracy theory but pretty much ruin his entire reputation” (VICE).

In 2014, in an interview broadcasted with Democracy Now!, journalist Robert Parry stated: “We saw a complete failure, perhaps one of the most shameful examples of how the mainstream press can operate in destroying a fellow journalist for getting at an important story. And Webb suffered mightily for this” (VICE).

Clearly, the freedom of the press did not apply to Webb’s revolutionary work, with the focus of the CIA’s drug involvement getting lost. In fact, the media affair played out so well for the agency that an internal CIA publication named “Managing a Nightmare” referred to the episode as a good example of managing a public relations nightmare.

In 1998, the CIA’s own inspector general released a report admitting that most components and “theories” of the “Dark Alliance” publication were true. According to the San Francisco Examiner’s 1998 report of the released document, “The CIA’s responsibility for our drug plague did not involve giving an ‘order’. Rather, it involved obstructing the efforts of those who tried to combat drug trafficking” (VICE). Essentially, the agency had known that people linked with the Contras were importing cocaine, had done nothing to stop them, and had even gone as far as to protect them from the investigation.

In the same 2014 interview with Democracy Now!, Robert Parry belatedly reveals his frustrations: “So you had the CIA finally coming to the table and admitting that what we reported in the 80s and what Webb reported in the 90s was, in fact, true.”

In 1996, on the Montel Williams Show broadcasted on CBS, Michael Levine, author of the Triangle of Death, an investigative piece on the drug trade, stated: “Mr. Meneses was actually indicted in 1984. He was known within—my own sources in the DEA told me— he was known as ‘El Rey de La Droga,’ the King of Drugs. He was in more than 40 files and indicted mysteriously. And people within the DEA say that it was CIA intervention that kept this sealed indictment from ever being opened” (VICE).

In a case described in the report, when traffickers linked to Norwin Meneses were busted in San Francisco in 1983, the CIA even requested that ten thousand dollars seized be returned to the drug traffickers.

In the same interview with the Jim Norton Show in 2014, “Freeway” Rick Ross explained the agency’s involvement:

Ross: The CIA admitted that they knew that these guys were selling drugs and had went to the attorney general and asked the attorney general could they not report it because the mission that they were trying to accomplish was so big, it was a matter of US national security.

Norton: So, the US, the CIA was allowing this just kind of to happen, the drugs to go in. And they weren’t putting it there, but they were allowing it to happen and funneling the money?

Ross: [Vigorously nodding head] That’s what we believe.

The CIA did not actually sell crack themselves, but they did protect those involved in the drug trade and permitted the commodification of cocaine, sacrificing the lives of millions of Americans to not only the drug itself, but the societal chaos that would soon erupt.

What Exactly Does This Mean?

The most disappointing result of this scandal was the lack of consequences. After admitting to protecting prevalent dangerous drug dealers, the CIA got away with their illegal activity scot-free. No one in the CIA was fired or penalized. In the end, the CIA’s involvement in the drug trade spurred hundreds of laws and legislations that targeted minorities; the cocaine epidemic devastated the African-American community and established a systematic cycle that continues to prevent impoverished blacks and other depressed populations from escaping a fate already decided for them. A fate that entails an endless and meaningless struggle against poverty, a subpar education system, and a societal struggle against racial stereotypes.

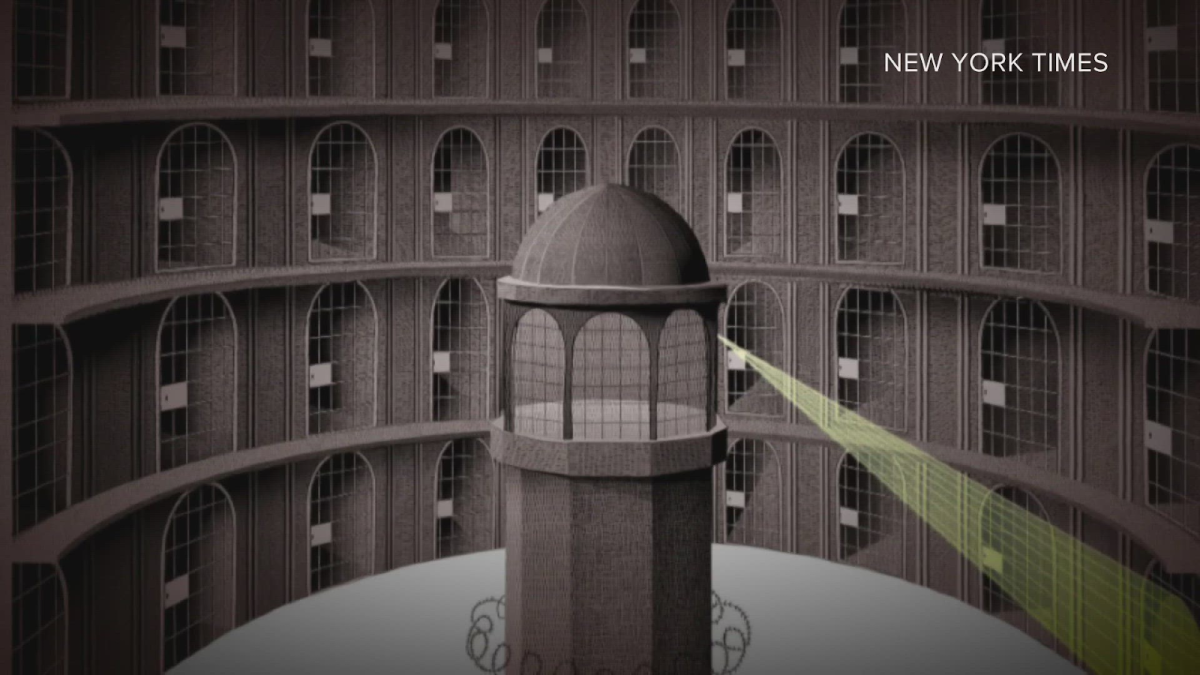

Part of the introduction of hard illicit drugs can be traced back to the CIA’s protection of key drug traders in the late twentieth century. And the “pervasive racial targeting” that followed its introduction, including the over-incarceration of African-American men, is its result as well. The number of black men incarcerated in 2001 (792,000) already equals the number of enslaved black men in 1820. Arguably, immersing African-American communities in addiction became a new method of controlling, subjugating, and punishing the African-American community. Black men are being incarcerated at unprecedented amounts, with 1 in 3 men incarcerated between the ages of 20 and 29 (The Drug War is the New Jim Crow). Americans across the country are in agreement that the war on drugs, and the determination to defeat their opponent, is of the utmost importance; similarly, most agree that rapid incarceration is the solution.

Property rights have also been scrutinized with the possession of any property now deemed as “guilty.” In fact, “all assets suspected of participating in a crime can be seized and sold, with the profits flowing to law enforcement budgets” (The Drug War is the New Jim Crow). The effort to win the war on drugs has shifted from criminal prosecution to the seizure of assets. In fact, by the late 1990s, many drug enforcement agencies received more money from the forfeiture of these assets than they received from their budgets (VICE). The war on drugs is, in reality, a targeting of the African-American and Latino community economically, socially, and politically.

Furthermore, it begins to seem as though the over-reliance on the drug trade as a means of profit and success in poor communities is intentional. With fewer opportunities, abysmally funded schooling, and an inescapable cycle of drug use in their communities, the options of African-Americans and Latinos alike, are exhausted and exploited. Families are left with the choice of participating in the drug trade or gambling on the lackluster and decimated education system provided to poor communities. Isabella Gonzalez Montilla, journalist, and reporter for The Borgen Project, a non-profit organization working on the alleviation of poverty in the US, explains that the relationship between drug trafficking and the community is complex and often a matter of life and death: “In this case, life is the sense that one can either remain in their impoverished life while death is where if they do not take on this illegal activity, they will die with the few resources they have”(The Link Between Drug Trafficking and Poverty).