“I don’t want my hijab to impact my future,” Areej Abukwaik uttered as she wrapped her arms around a pink fringed pillow, chin rested on both hands, eyes fixated on the camera. The dark purple color of her shirt coordinated perfectly with her lighter shade headscarf—she remained poised even as she shared her fears of being visibly Muslim. “I just don’t know what I would say if someone were to call me a terrorist,” she said in a wobbly voice, “Do I ignore it or do I fight back and become the stereotypical aggressive Muslim?”

From looking at the mirror plastered with stickers leaning against the cheerful blue and white striped walls of her room, one would think of Areej as your American average teenager—which she is. Yet amidst the rising Islamophobia in the U.S., Areej Abukwaik has been forced to deal with a burden far beyond the understanding of her peers and even most adults. She divulged that being visibly Muslim comes with “the constant stares from strangers and knowing that people cross to the other side of the street just to avoid being near you.”

As John Lennon’s “Imagine” played from my headphones, I leaned closer to my computer screen. The headline of the Washington Post article left me with a pit in my stomach: “Georgia officials were set to approve a new mosque—until an armed militia threatened to protest.” When I brought this up to Areej, the video seemed to freeze. Her brows drew together with disbelief and she quietly stammered, “Wow I can’t believe people hate Islam to the point where they would bring weapons outside our place of worship. It’s horrible knowing that because of the religion, I am hated by many and seen as dangerous. Why should I be seen as a threat by the people around me just because of my faith?”

Areej leaned forward toward the camera, nearly filling the entire screen of my phone. She began to discuss the anti-Muslim sentiment in Western news, explaining that “when a white man walks into a school and opens fire, he gets to be labeled as ‘mentally ill.’ But if the man was Muslim, the media would call him a terrorist—no questions asked.” In noting the lack of empathy towards the Muslim community, her voice took on a clipped tone. “Where was the global outrage at the Christchurch mosque shootings? If the circumstances were different, and it was an anti-Christian shooter entering a church, the story would have spread like wildfire. In a way, it seems as though the media doesn’t care if Muslims get killed, but would consider the deaths of each and every Christians to be tragic.”

Aside from news, other forms of media such as films and TV shows unfairly stereotype Muslims. Instead of challenging the image of the “oppressed” woman or the violent Middle Eastern man, mainstream films and TV shows capitalize on these stereotypes—leaving viewers with a single, inaccurate perception of the Muslim community. The overused story trope of a Muslim girl who is “saved” from her religion couldn’t be further from Abuwaik’s reality. “I chose to wear my hijab when I was 13–not because anyone forced me to—because I wanted to. My hijab is not only a symbol of my faith, it is also an important part of my identity. I am proud to be a Muslim.”

While it’s one thing for the media to promote anti-Muslim biases, it’s another for major political figures to do so. When asked in an interview by CNN’s Anderson Cooper whether he believed Islam was a threat to western nations, President Trump responded, “I think Islam hates us. There’s something there that—there’s tremendous hatred. We have to get to the bottom of it. There’s an unbelievable hatred of us.” The President of the United States sets an example for U.S. citizens to follow; his words matter. Whether it’s said in a tweet or whether it’s said in a interview, it all comes together to create an environment where it has become accpetable “for students at to school to call my sister a terrorist and for a woman at the pool to call another hijabi a ‘stupid towel-head,’” Areej said with a grimace.

When asked, “Have you ever worried about how wearing a hijab would change the way people treat you?”

She replied, “Yes, of course. With the rising Islamophobia in the United States, I mentally prepare myself for people to be hateful. I’ll imagine a scenario where someone says something rude, and then I’ll think of ways to respond. I even feel as though I have to constantly paint this happy image over my face in order to convince the people around me that Muslim women are not opressed, are not dangerous, and are not terrorists. I have to prove to them that Muslims are peaceful people and deserve to be accepted in society.”

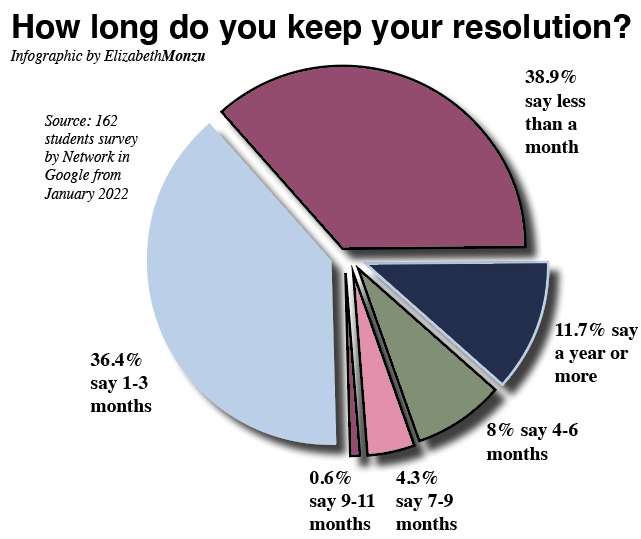

People often say we study history to prevent it from happening again, but fear and discrimination of minorities seems to be an exception. A century ago, Americans viewed Catholics the same way they now view Muslims. In the mid 20th century, Jews were blamed for multiple issues, including the Wall Street crash and WWI. According to The Economist, “in 1939, 61% of Americans opposed offering Jewish children asylum, slightly more than those who oppose accepting Syrian refugees today.”

In response to these often overlooked pieces of American history, Abukwaik reflects, “For a nation that’s supposed to have ‘liberty and justice for all,’ we have quite the contradictory history.”

The truth is if you’re a “normal”, white American, you don’t understand what it’s like to be Muslim or any other minority for that matter. Maybe confronting this reality makes you feel guilty, but it doesn’t have to be that way. You can choose to never experience the shame that stems from turning a blind eye to prejudice.